And so the bells were silent

Susan Hall

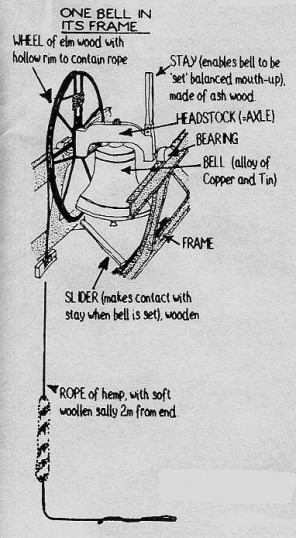

Bell ringing, or rather, change ringing origins lie in the sixteenth century when church bells were hung with a wheel. This gave the ringers control of their bell, which allowed sets of bells (rings) to be rung in a continuously changing pattern.

Music is created by moving bells up and down the ringing order of a defined sequence of changes known as a method. Learning a few simple methods allows ringers to join in with other bands in towers around the world.

Being a ringer gives a great mental and physical workout, maintains a traditional skill and offers the ringer a lifelong experience, it is well within the capabilities of most people, ringers come from all walks of life and range in age from ten to those within their eighties and some their nineties.

The initial teaching takes several weeks, after which the learner can begin to ring with the rest of the band. Most ringers practice once or twice a week and ring for Sunday service.

There is a social side to ringing, going on outings to experience rings at other towers, meeting other ringers, entering competitions and taking part in celebrations, for example, weddings, the start of the Olympics in 2012.

Because bell ringing is a team activity, you are in close proximity to each other and you handle a rope, which is shared by other ringers, the ideal environment to spread Covid-19.

So on 14 March 2020 most bell ringing communities ceased ringing bells in churches, and on 23 March, the Archbishops of York and Canterbury instructed churches to lock their doors. All church service had to stop and all bell ringing had to stop until further notice.

All weddings were cancelled, all celebration ringing was not allowed, this included 8 May, VE Day. The clergy were not permitted to enter their churches anymore, services and prayer had to be done remotely.

The Central Council of Church Bell Ringers issued the following advice that the current suspension of all ringing of any kind should remain in place. This includes chiming of single bells and the use of Ellacombe chimes.

The key issues which affect the safety of ringing are the physical environment of towers including access to ringing rooms, the space between ropes, how to maintain hand hygiene in towers and the numbers of people in a restricted space for a relatively long period of time. Even if churches reopen, the environment in towers is very different.

This is not the first time bells have had to be silenced. In the past it was for a much different reason.

The Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) of 1914 governed all lives in Britain during World War One. The Defence of the Realm Act was added to as the war progressed and it listed everything that people were not allowed to do in time of war. As World War One evolved, so DORA evolved. The first version of the Defence of the Realm Act was introduced on August 8th 1914. This stated that:

no-one was allowed to talk about naval or military matters in public places

no-one was allowed to spread rumours about military matters

no-one was allowed to buy binoculars

no-one was allowed to trespass on railway lines or bridges

no-one was allowed to melt down gold or silver

no-one was allowed to light bonfires or fireworks

no-one was allowed to give bread to horses or chickens

no-one was allowed to use invisible ink when writing abroad

no-one was allowed to buy brandy or whisky in a railway refreshment room

no-one was allowed to ring church bells

the government could take over any factory or workshop

the government could try any civilian breaking these laws

the government could take over any land it wanted to

the government could censor newspapers

As the war continued and evolved, the government introduced more acts to DORA.

the government introduced British Summer Time to give more daylight for extra work

opening hours in pubs were cut

beer was watered down

customers in pubs were not allowed to buy a round of drinks

Back in 1940, during World War Two, bell ringing had to stop. The reasoning behind it was not really understood and on 31 March 1943, it was debated in the House of Lords

“THE LORD ARCHBISHOP OF YORK, moved to resolve, that the ban on the ringing of church bells should be now lifted or modified. The most reverend Prelate said: My Lords, in moving this Resolution I want to make it quite clear at the very outset that I am not moving it on the ground that all danger, either of invasion from the sea or from the air, has passed away. When a wild animal is wounded it is then most dangerous, and of course it is quite possible that in the months to come every kind of attack will be made upon this island. My reasons for moving this Resolution are different. I am moving it because I wish to submit to your Lordships that in a large number of cases the ringing of the church bells would give no kind of useful warning, that in other cases where the bells might be useful in that way they could be rung without interfering with the ordinary ringing of the bells, and that therefore it is both unreasonable and unnecessary to silence bells which for centuries have been so closely associated both with the religion and life of the country.

I would remind your Lordships that when this edict about ringing the bells came into force it was at a time of great strain. We had evacuated from Dunkirk where we had lost an enormous amount of equipment. It was possible that at any moment the French might cease fighting. I think an historian when he looks back on that period will pick out the utterance of the Prime Minister that we should go on fighting, if need be alone, and that we should fight on our shores and in our lanes, as one of the most striking and decisive utterances in the whole of our island story. The historian, looking back on that period, will, I think, also be struck at the calmness, the complete lack of all panic, with which every village and every hamlet prepared to meet the possible invader. But of course during that time many decisions were made which afterwards were found to be unnecessary. I am not for one moment criticizing those who at that time made the decision that the bells should not be rung and should be reserved for giving notice of an invader from the air. Since then many things have happened. Many regulations which were laid down at the beginning of the war or at that time have been either removed or modified. It is no longer necessary for us to carry our gasmasks at all times and in all places. Even sign posts are beginning, it is true somewhat shyly and coyly, to point timid fingers to towns which no one could mistake. Those of your Lordships who have exceptionally good sight may occasionally from the train able to discern the name of some station, and blocks which at the time were erected on the assumption that the enemy would naturally proceed along the roads and would not trample on the growing crops have been removed to more suitable places. But amidst these very varied changes and modifications one ban remains unchanged.

For nearly three years 12,000 parishes have had their bells silenced, in case in one of these parishes there might come from the air a certain number of Germans. There have been three exceptions. On one occasion certain bells were rung by mistake; the bells were rung to celebrate the victory in Egypt; and they were rung again last Christmas. But with these exceptions, for nearly three years no bells have been rung to summon the people to worship, no bells have been pealed at weddings, no bells have been tolled for the dead, no bell has been rung at the induction of a new incumbent, no bells have been rung from college chapels. All over the country there has come a silence to our bells. There are, of course, some people who hate bells and they will regard the silence of the bells as one of the only alleviating compensations of the war. But the great majority of people deplore the silence of the bells. We who are members of the Church of England regret most deeply that our bells are not allowed to be used in the tradition away to summon people to worship. It is, however, not only members of the Church of England. There are large numbers of people who are not greatly interested in Church matters who miss the bells, and that is specially so in the country districts. Psychologically I am quite certain this silence of the bells has a very bad effect on the people.

Of course if the noble Lord who is to reply for the Government tells us this is a matter of national security, and also gives us the reasons why it is necessary for national security that the bells should be silent, I have nothing more to say. We are ready for our bells to be silenced if silence is really going to help the national cause; but I hope the noble Lord will give us some reasons why and how this ringing of the bells if the enemy should come from the air is to help. From the Regulations which have been published I understand that the bells are only to be rung if some twenty of the enemy land. Then the bells are only to be rung in the parish in which they have actually landed. I ask your Lordships to consider this in the light of cold reason. Out of the 12,000 or 13,000 parishes, about 4,000 are town parishes. How is this going to help in the towns? In a town it is not always easy to know the ecclesiastical boundaries where there are a number of different parishes. When I went to South London I soon found that the people of the parish rarely knew where their parish church was, and at the risk possibly of some misunderstanding I had for a time always to ask for the nearest public-house. It is difficult to know which church belongs to which parish.

Suppose in London or in any large centre of population some Germans came down from the air. What would happen? First of all the air raid warden—I am not quite certain who is the responsible person—or the policeman would have to be certain of the exact number. Secondly, he would have to consult a map of the parish, and then he would have to hurry to the parish church and risk his life, if he is not a bellringer, by ringing the bells. Even suppose the bells were rung, what help would that give? Suppose Germans had descended on the roof of South Africa House, what help would it be to us at Westminster or Lambeth if the bells of the parish church were rung? Or if the Germans landed in the back gardens of some street in the East End of London, what help would it give if the bells of St. Matthew’s were rung? It may, perhaps, be retorted that I am giving a caricature of all this; that it was never intended that these bells should be rung in towns as a warning but should only be rung in the country. Very well then, why ban the ringing of the bells of the town churches? Let the bells of those churches which are in the towns be rung.

Now I turn to the country districts. Here, of course, the conditions are different. Most country people know the boundaries of their parishes. They know the brook, or the field, or the wood which separates them from the neighbouring parish. Often they look upon those living in a neighbouring parish as foreigners, and, possibly, as a rather inferior class of people. But they do know their own parish boundaries. There is no difficulty over that. But in many cases these country churches have bells which are by no means strong and which cannot be heard at any considerable distance. Many of these parishes cover very large areas; often there are valleys and hills in them, and sometimes, of course, the wind may be in the wrong direction. The result will be that if these bells are meant to put people on the alert—and no one seems to be quite clear why the bells should be rung, and what the response to them should be—that result would not always be achieved. In many of these parishes a number of people would go on working away in the fields in complete confidence without hearing the slightest sound from the bells which are supposed to give them warning of danger.

I admit that there is a large number of churches to which this objection does not apply. There are numerous parishes where the churches have bells which can easily be heard over a considerable distance. But surely those bells can be rung in a different way when a warning is to be given. In the Middle Ages church bells were often rung to give warning of the approach of an invader, and, down to much later times, to give warning of fire in the town or village in which the church was situated. The bells can be clashed or clanged in a quite unmistakable way. No one in the country could possibly confuse the ringing of the bells for an alarm with the ordinary ringing for Divine Service if this was done. I do not know if the noble Lord who is to reply on behalf of the Government is himself a bell-ringer. But if he has any doubt about this point, and he is not a bell-ringer himself, I venture to say that if he tried to ring the bell of the nearest parish church the noise that the bell would make would strike consternation into the hearts of all who heard it, and no one would mistake the result of his efforts for ordinary bell-ringing.

What do I ask the noble Lord who is going to reply on behalf of the Government? I ask him, in the first place, if possible, to tell us that they are going to lift the ban entirely from all these bells. The ban, I would point out, could be put on again very promptly; a few hours’ notice given by means of the wireless would be all that would be necessary. At any rate, I suggest that the ban might be lifted for a time. If it is not possible for the noble Lord to tell us that, then I would ask the War Office, or whoever it is who is responsible, to lift the ban so far as it affects the town churches and to allow the bells in the country to be rung on Sundays or on the occasions of great festivals. At the same time that this permission was given, there could go out an order saying that the bells were not to be clashed or clanged except when required for warning purposes. If the very worst comes to the worst—I do not want to put this House to the trouble of a Division—and if the noble Lord cannot give me those assurances, I hope he will give an assurance that in the light of these facts, and in the light of what I have no doubt other members of your Lordships’ House will say in this debate, the whole matter will be most carefully reconsidered.

I have to admit that if permission is given to ring the bells at once, in many instances it will be impossible for the bells to be rung immediately. The men who used to ring them are now, in many cases, serving their country in the Forces. Nevertheless, I am quite certain that, somehow or other, most of the church bells would be rung on Sundays. People would be found who can ring bells, and there are many of the soldiers stationed in our villages, who would be very glad to ring the bells there just as they were accustomed to ring them in their own home districts. I hope the noble Lord will give us an answer which will show that very soon it will be impossible for the enemy to say that he has, at any rate, silenced our bells. I hope the noble Lord will give us an answer which will mean that the bells will once again be able to ring forth their message of faith and hope through the length and breadth of the country. I beg to move.

Moved to resolve, That the ban on the ringing of church bells should be now lifted or modified.—(The Lord Arch bishop of York.)

My Lords, the most reverend Prelate asked me to support this Motion, knowing my personal interest in the matter. I have repeatedly urged that these bells should be rung again, and I submit that the most reverend Prelate has made out an unanswerable case. In regard to one thing which he has said, I believe that I can comfort him and at the same time challenge the noble Lord who is to reply on behalf of the Government. I am not sure but I believe what the noble Lord who represents the War Office in this House is going to reply.

THE PARLIAMENTARY UNDER-SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WAR (LORD CROFT)

Yes, that is so.

I have something to say which I think will throw a light on this matter. The most reverend Prelate said that, of course, if it could be shown that there was some real military reason which made it dangerous to remove the ban on the ringing of the bells he had nothing more to say, but otherwise—because he, like all the rest of us, wants them to ring again seeing that the ringing of them adds to the joy and happiness of our lives—he would press his Motion. Since I last addressed your Lordships on the subject, I have made certain inquiries of intelligent soldiers occupying high positions, and I say definitely—and in doing so I challenge contradiction—that to rely seriously on church bells as a means of giving warning would not only be not an advantage but would he a positive danger, as matters stand. If the most reverend Prelate’s Motion he accepted the result will be to add to the security of this country instead of diminishing it.

I think I can make good my case, In the course of conversation with an intelligent soldier I said to him: “We are all puzzled about this question of the ringing of church bells.” He replied: “Oh well, the Prime Minister likes to be able to tell you to ring the church bells to celebrate a victory.” I said: “Yes, that’s all very good no doubt lout that is not going on.” To this he replied: “Of course, as a military expedient it is; frankly ridiculous. For be it observed.” said the soldier, “that if you want a warning to warn you of the presence of the enemy, certain things are essential. The first is that you must know whence that warning emanated; secondly, you must know that the means of giving the warning are in good order, In the case of church bells, neither of these conditions is fulfilled. If I am to be asked to regard this as a serious matter, then I must ask that all the 12,000 churches shall be properly guarded by the military, in order to ensure at all moments that the bells are not rung by Fifth Columnists or reckless people. Secondly, I must be given authority to put those 12,000 belfries in order.” I said: “Do you understand that in many cases the bells will not ring?” He replied: “Yes, I am advised that in a great number of cases either the ropes would break, or the bells would fall through the roof on to the heads of the people below.”

I do not know what action the noble Viscount, the Leader of the House, is going to take in this matter, but I think I am entitled to make a challenge to him as Leader of the House. If what I have said is true—if no sound military opinion can be found to say that we ought to rely upon church bells as a warning—I think that we ought to be told. If it is alleged that there is some sound military opinion which says that we should rely upon church bells as a warning, then let us be told the name and rank of the military officer who says: “We desire to rely on church bells as a warning.” I know that I am placing the noble Viscount in a difficult position, because I am perfectly aware that there is no such military officer in existence. Nobody who considers the matter can possibly regard this as a sensible method of giving warning of the enemy’s approach, unless the steps which were described to me are taken to ensure that it shall be efficient. Imagine the enemy arriving, and it being said that the church bells must be rung. You will first have to ask whether the Germans have fulfilled the necessary conditions, because I am told that there are three or four different conditions which must be fulfilled before the bells are rung. Finally, when the military Commander gives the order for the bells to be rung, imagine the fantastic moment when the man runs to the belfry, pulls at the rope, and down comes the bell and cracks his head. Are we going on playing this childish opera bouffe, and thus robbing ourselves of a certain measure of pleasure and satisfaction?

My noble friend Lord Samuel, who I understand takes the same view as I do on this matter, reminds me that all over the world at different times the tocsin has been rung in order to warn people of intending revolution or of revolution itself. At this moment, throughout Switzerland, where the danger of fire is very great, it is the bells which give the warning by clashing. But if anybody in Switzerland were to suggest that the ringing of church bells in the normal way should be stopped, he would be voted a fool, because it is only by the constant ringing of them at the settled times of divine worship that it is possible to make sure that they are in working order. For all these reasons, I beg the Government to make the position quite clear. I challenge them to produce the authority of a named distinguished soldier who thinks that this is a good plan, and I cordially support the Motion of the most reverend Prelate.

My Lords, I should like to be allowed to say one word in support of the most reverend Prelate, but I shall not detain your Lordships for more than a few minutes. It certainly seems to me that people have overlooked what has been referred to by the noble Lord who has just spoken and by the most reverend Prelate, that there is a great history behind the use of bells for purposes of alarm in cases of public danger or public excitement. In France, for example, it was the bells of St. Germain Auxerre which started the Massacre of St. Bartholomew, and we do not hear that there was any confusion. We do not hear that devout ladies arrived at the church expecting an early Mass, and accosted the verger and were informed “No, ma’am, there’s no early Mass, it’s the Duke of Guise’s people, I think, who are ringing the bells; some trouble with the Huguenots, I fancy,” and so the poor ladies had to go home unconsoled by devotion. We hear of nothing of that kind. No confusion arose; the massacre went forward with its usual business like efficiency, quite untroubled by any misapprehension as to the ringing of the bells. In the French Revolution, the tocsin was used repeatedly for purposes of alarm. Nobody made any mistake; everybody understood the ringing of the bells, as they were intended to understand it.

Indeed, bells are very expressive things. It is very easy to express human purpose and emotion by bells. Most of us do not now use the old-fashioned bell which used to be rung to summon domestic help, but those who have used it know how easy it was to distinguish between the rebuke for neglect or delay and the mere admonition regarding some detail of domestic routine. These things are quite easily expressed with bells, and I do not think that there would be the smallest difficulty in ringing a bell in such a way as to bring everybody into the streets—and that is all that a bell could be used for. I entirely agree with the noble Lord who has just spoken, and with the most reverend Prelate, that you cannot use a bell for military purposes; you can use it only to bring people into the street, and you can easily express your feelings of alarm and anxiety by ringing the bell in a tumultuous manner. Indeed the ingenious poem of Edgar Allan Poe is there to show that the different expressions of bells can even be represented by metre and verse, so that they must be perfectly distinguishable the one from the other.

I think, therefore, that this regulation might well be modified without the smallest danger of depriving the resources of defence of whatever benefit they now derive from the silence of the bells, and I strongly agree with the most reverend Prelate that to multiply regulations which are not necessary is unwholesome from the point of view of public morale. Your Lordships will remember the lady in the Ingoldsby Legends who did not mind death but could not stand pinching. I think that that is very typical of human nature. It is not the great danger, it is not the fear of something very terrible, that demoralizes people; it is the constant vexation of petty restrictions. I hope, therefore, that the Government will, in the public interest, whenever it is possible to remove a regulation which causes annoyance, hasten to do so. I am sure that there is not a parish in the country which would not echo the desire of the most reverend Prelate and respond most cheerfully and most intelligently to a permission to use the bells for their proper purpose as a summons to devotion.

My Lords, you may be interested to hear the origin of the order about the ringing of the bells. It was at Tunbridge Wells. Lord Ironside, who was then Chief of the Imperial General Staff, was in my room, and there were also present General Thorne and, I think I am right in saying, my noble friend Lord Knollys. We had just got the first detachments of the Local Defence Volunteers formed, and the only part of the Local Defence Volunteers who had arms at that time were the Kentish and some of the Sussex Companies. The whole thing was very nebulous, and it was thought that at any moment we might see parachutists dropping down from heaven. I think it was the Chief of the Imperial General Staff who said: “How are you going to get these Local Defence Volunteers together if parachutists suddenly appear?” and somebody in the room—not I, but I could not be sure which of the others—said, “Why, we will ring the church bells, until we can think of something better.” That was early in May, 1940, and the War Office have been thinking of something better ever since. That signal at that time was supposed to be used only in the Counties of Kent and Sussex and in the rural areas, but somehow or other the order became more or less sacrosanct, and spread all over the country. It was trimmed and pruned, and sprouted new legs and arms, and it became one of the essential pillars of the defence of the country. It is a complete mystery to me why that should be se, but I am assured by War Office representatives that it is.

Like my noble friend Lord Mottistone, I have a great interest in this regulation, as I was present at its birth. I have asked one high soldier after another what he thinks of it. I would hesitate in your Lordships’ House to quote most of the replies, but none of them was complimentary. I found when I was in the North-Western portion of England that over a large part of that region at any rate any idea of ringing the church bells in any circumstances connected with the arrival of any Germans had been abandoned, because it was obviously an impossible way of communicating information to anybody who was wanted. There was a very elaborate system of calling out the members of the Home Guard who would be required. I should like very strongly support the Motion moved by the most reverend Prelate. I am quite certain that if an investigation of the facts were made you would find that nobody really knows what this regulation is supposed to do; that it is merely kept in force because it is in force, and nobody will take the responsibility of agreeing to take it off.

My Lords, very careful consideration, as most of your Lordships know, has been given to the subject raised by the most reverend Prelate. The matter has in fact been raised very frequently, and actually several times this year, in another place. Consequently I can assure your Lordships that the whole question has been reviewed very often under the changing circumstances of the war. Every form of alternative warning has been considered, including of course the variation of the use of sirens, but none of these alternatives has been found to be satisfactory. We have had a most important debate, if I may humbly say so of very high quality, with most interesting suggestions from many quarters, and I will bring all those suggestions to the notice of my right honourable friend the Secretary of State. My noble friend Lord Mottistone, who has always been very interested in this question, remarked that the most reverend Prelate had stated that if there was any real military reason for this regulation he would not press this Motion, and I think we all know that. But Lord Mottistone proceeded to say that an intelligent soldier—he did not give any indication as to who it was, but he occupied a very high position—gave him a certain opinion upon the subject. He asked me to state the name and rank of the soldiers who advised His Majesty’s Government. That, coming from an ex-Secretary of State, seems to me to be a most unusual question. I doubt if he really meant it, but of course I must take the responsibility here for my right honourable friend in another place. The last thing in the world we could do would be to pick out one particular person and say “This is the officer who is responsible for this or that view.”

My noble friend appeals to me as an ex-Secretary of State not to ask for the name of a particular officer. Of course I do not ask him to say “Lieutenant-General Binks is the man who says that these church bells are valuable for a warning,” but I do ask him to name the particular authority who says it is wise to rely on the church bells.

I most emphatically say I cannot give any such information. I speak on behalf of the Army Council, and I take the political responsibility in this House. I, too, like the most reverend Prelate, greatly miss the ringing of the church bells. I have taken, therefore, exceptional opportunities when inspecting various Home Guard units all over the country, to make inquiry in order to try and get a general impression. I must confess that again and again I have heard discussions as to whether there is not some alternative method which could be used by means of the siren, or whether there was any other specific warning which could be given, and I have not in all my large-scale peregrinations come across the view which was expressed by the noble Lord, Lord Geddes.

I will give you some addresses if you like.

I shall be only too pleased, because I take this debate very seriously, and I would like every suggestion which has been made to be examined. I will give a pledge that that shall be so. But the answer to the question as to whether the ringing of the bells is considered to be of military importance is the fact that my right honourable friend has done just what Lord Mottistone would have done in his place; my right honourable friend and the Army Council have tried to take the best military opinion of all Commands, and on that military opinion they have founded their decision. We share the desire of the most reverend Prelate that church bells should again come into general use, but so long as we are convinced that this is the only signal which can be regarded as a distinctive and definite warning no alteration in the existing arrangement can be made. I should like to say, however, that in view of the powerful speech of the most reverend Prelate, the exhilarating and witty thrusts of my noble friend Lord Quickswood, and the emphatic statements of Lord Geddes, I will bring all the arguments that have been used to-day before I my right honourable friend and will tell him what great interest those speeches have created in your Lordships’ House.

THE LORD ARCHBISHOP OF YORK

My Lords, I am naturally disappointed at the answer which has been given by the noble Lord. He has really simply repeated the statement we already know, that this is regarded as almost a military necessity, but he has not given us any reason in support of that view, and he has not told us why an alternative kind of warning would not be sufficient. He has not told us why the bells in all the towns should be silent, even if it is necessary for the bells to be rung in the country as a warning, but he has told us that this matter will receive most careful and full consideration. He has given a very definite pledge to that effect. In view of that pledge, and in view of his own interest in this subject and his sympathy with my object, I shall not press my Resolution at this moment. But I hope in the near future it will be possible for the noble Lord to make some further statement on the subject. If some satisfactory statement is not made in the near future I shall be bound to bring this matter up again and take it to a Division. I ask leave to withdraw the Motion.

Motion, by leave, withdrawn.”

Although this motion was withdrawn this ban was lifted temporarily in 1942 and permanently in 1943 by order of Winston Churchill.

In September 1939, St Peter’s Church, Tewin has a quote from Mears and Stainbank, Whitechapel for the making and fitting of a new treble bell. Although this quote went ahead and the bell was fitted in 1939, it was 1945 before it ever got rung.

Add your comment about this page